On Writing and Books

New, Used, Rare

Lots of happenings here this week I could write about.

I passed by a riding lawn mower wheels up in a ditch with a pair of legs sticking out, and when I circled back and righted it, a bruised but grateful neighbor popped up. It was ten in the morning, but he smelled of booze. I’ve been there, buddy.

Our bathroom has a skylight over it and the other day my wife paused her singing and called me in as she showered to show me an actual rainbow arched like a halo above her head. This left me pondering many things.

The hibernating wasps in my woodshed that I wrote about to kick off this Substack endeavor have awakened and are multiplying and causing much comical and sometimes emasculating mischief that will only worsen into summer.

My truce with the deer is holding so far, and in a moment of premature optimism I purchased and planted a hydrangea, only to wake the next morning and find it gone. Not eaten, just gone. The whole plant. Root ball and all. Only the hole I dug remains. Have the deer started their own garden? Are they using shovels now? No, it must be something else, but what gremlin ran off wholesale with this plant I’m not sure I want to know.

Then on Saturday night my wife and I ferried across to meet up with city friends for what we thought was going to be a quiet dinner to catch up, discovering too late that the steakhouse chosen was modeled on something from South Beach. I sat on top of a subwoofer and pantomimed with a backdrop of half-dressed servers twirling sparklers for three hours, attempting to lipread as a workaround to the thump thump thump that still pounds deep in my aching ears. The food was good but way too salty, and I was up all night downing pint glasses of tap water.

Perhaps the ripest episode to explore would be the email I received just now from Mary and Christian, a telepathic (and photogenic, I must say!) duo, offering to use their “privileged connection with the Celestial World” to unveil the name of my guardian angel and the secret message he has for me; and that I briefly considered taking them up on the free offer, despite knowing full well that it must at least involve a small convenience fee.

But what I’m really thinking about this morning, and what I’d like to write a little on, if it’s even possible, is writing itself. I know some of you are fellow writers, and I suspect others may find the topic interesting, or at least less toilsome than a golden palm reading performed via Skype.

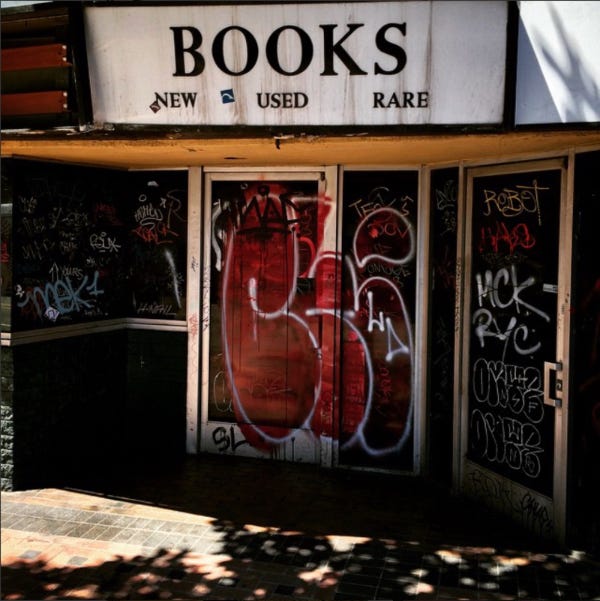

First, to break up all this text, a photo I took on my way to a Bob Dylan concert in San Antonio.

And now a brief bit of personal history.

When I was cutting my teeth as a novelist I fell in with a group of poets and writers, many of whom had been working at their craft for a half-century or more. We would meet twice a week to read pages of our work, exposing it to harsh but honest criticism, followed by timed-writing exercises in the style championed by Natalie Goldberg. Then my work started selling and our relationship broke down. I showed up the same as I ever did, but the group treated me differently. A few appeared to believe I had found some hidden door into publishing success, and then took offense when I refused to share my secret. Others seemed envious or just aggrieved that a young upstart had stumbled so easily into the literary career they had spent decades pursuing. Whatever the cause, it was a sad epilogue to an otherwise happy story.

Looking to replace the broken fellowship, I signed up for a novel writing course at a storied community writing center in Seattle. The instructor and the students were fine people, but they spent almost every class discussing TV shows and their plots, hardly mentioning a single book. And when we did read pages of our work, it was clear that the critique I had come to rely upon from my prior group was not on the menu, and was, in fact, off limits, replaced instead by empty calories of encouragement. I was hoping for someone to tell me when my work was crap, not pat me on the back and then shape that crap into a fantasy treatment for the next imaginary hit on Netflix.

Adrift again, I landed on a couple of sites hosted by lauded university professors with PhDs in English Lit who were offering interactive lessons online. It quickly dawned on me, however, that one can know too much about the mechanics of their craft. That’s evidenced by English departments often producing great editors and teachers but lousy writers. Anyway, it was all gibberish to me. Perhaps I’m just not ready to analyze the structure of English texts since I don’t understand subordinate clauses, infinitives, gerunds, interrogative pro-adverbs, and am still looking to demystify the ever-elusive semicolon; but if even I could, whither, I wonder, dear professor (or is it hither?), does any of this even lead?

You can learn a great deal about human anatomy on the dissection table, no doubt, but you can’t produce a baby with all that knowledge. It takes something more instinctual, more primal. If you ask an eagle how it flies, it can’t tell you, and I suspect that if it could, it would immediately fall out of the sky. I had to ask myself, do I want to be an ornithologist, or do I want to fly? And so, I fled another nest.

So, what’s a writer, or an aspiring writer, to do? I generally feel like a teenage imposter trapped in a man’s body and am thus hesitant to dish out advice; but I’ve been asked often enough, even in messages by some of you here, that I’ve thought about it a bit and come up with a few things that have helped, and continue to help, me.

(Brief internal dialogue: Okay, kid, put on your adult mask. Now straight posture, look pensive, but not too serious, serious but also relaxed, remember your line: “I’m so-and-so, and this is my master class.”)

First, live your best life. Experience is crucial. If you have none, what the hell are you going to write about? And I’m not talking about gathering episodes for a memoir. I mean having some real-world experience to breathe into your characters and use to inform your plots. I’ve set aside many books because it was clear that the author’s experience was as shallow as the Wikipedia entries it came from.

“But I write fiction,” you say.

Yes, I know, and imagination is wonderful! But it has to be intertwined with and layered on top of this awesome and mysterious reality that no human, no matter how genius, could have conjured alone from the vast nothingness of space.

Second, talk less and listen more. Practice being a wallflower. A great many otherwise well-written books are ruined by poor dialog, the writing of which no school can teach. You either develop an ear for it or you don’t. And you must listen deeper than just the words or cadence or dialect, penetrating into the ways in which the human mind expresses itself through, or sometimes even hides itself behind, speech.

What are they saying? What do they think they’re saying? What are they really saying?

So on and so forth.

I overheard an exemplary exchange the other day between two tree workers who arrived here early and didn’t see me in the garage messing with my grease gun. I jotted it down in my notebook and am presenting it here with no dialog tags or attribution, just as I heard it blind from beneath my Jeep. (Fair warning, working men and women sometimes swear.)

“Do these glasses make me look Asian?”

“You are Asian, dipshit.”

“Half, actually.”

“Yeah, okay.”

“But seriously, do they make me look Asian?”

“Fuck, I don’t know. Is Josh bringing the bucket truck?”

“He didn’t say. So, you think no?”

“I think we’ll need it.”

“No, the glasses.”

“Fucking hell.”

“They do, right? They make me look Asian.”

“Is that what you’re going for?”

“Not really, but I think maybe they do.”

“Jesus Christ.”

“I’m just saying.”

“Can I just drink my coffee?”

“So, you don’t think so then. Or you do?”

“I don’t know, man. I don’t care. But I’ll tell you this, I’m looking, and they definitely make you look stupid.”

Obviously, dialog must often be shortened and dramatized, but you need to find a way to do that and have it sound real while revealing things about your characters. I knew quite a bit about these two characters by the time I crawled out from beneath the Jeep to introduce myself, and, of course, compliment the one on his glasses.

And finally, the most important thing I believe: read, read, read. Reading is where you learn the craft. Reading is where you pick up what works and what doesn’t. You cannot write well unless you are well-read. You don’t need to dissect what you read. You don’t even need to think about the writing at all. That’s all happening at some deeper level anyway, where it should happen, and where it’s best to let it remain unless you have a professor to impress. All you need to do is read. And not just in your preferred genre either. Read everything.

Perhaps most importantly, read the works that have formed the foundation of English literature. From Shakespeare to Steinbeck, from Beowulf to Elizabeth Barrett Browning, from Nathaniel Hawthorne to Anais Nin. And then read the Bible. Whether you’re a devout believer or an ardent atheist, the Bible is undoubtedly the greatest story ever told, and it is the headwater from which most everything written in English since its first translation flows. Every Great American Novel, every catchy Dylan tune, every Hollywood hit, every poem, be it penned by Robert Frost or Maya Angelou, no matter how tangled its path, no matter how far removed, can be traced back and linked someway, somehow to the stories in the Bible.

I read something the other day in one of these trendy online magazines about “decolonizing your bookshelf,” whatever that really means. But you can no more hope to decolonize the Western canon than you can to choose your grandparents. The very rhetorical devices employed in the article to make the author’s fragile case are born from the thing they seek to erase. Discard nothing. Add to it instead. Reading is not a game where one player must be retired for another to take the field. Read it all, starting with what interests you. And then if you want to be a writer, write, and poof! you are one. A good or poor one only fortune and time can truly tell.

I cannot reveal your guardian angel’s name, but I’ll share an absolutely amazing celestial secret with you. For less than two bucks you can download to your Kindle or computer The Complete Harvard Classics, a 70-volume anthology of hundreds of classic works and literary fiction, that in the words of the late Harvard University President Charles Eliot, its curator, provides the “best picture of the progress of the human race within historical times, so far as that progress can be depicted in books.”

Reading 300 words per minute, you can work through it all in about 1,000 hours. If the average teen spent just half of their social media time reading instead, they’d finish it in just two years. It’s my view that every anglophone child should receive an e-reader loaded with this collection to dip into if they’re curious, or not; but that anyone desiring a liberal arts education should at least be required to prove that they’ve read most of its forty thousand pages before being granted a single penny above two dollars in student loans.

Did I mention it costs two bucks? I know, I know, nobody wants to read that old stuff. I did skim over a few of the more tedious modern English dramas myself.

And now, If I may come down from my lectern to offer a piece of practical writing advice that I’ve paid much wasted ink to learn: Use as few adjectives as necessary, even fewer adverbs, and everywhere possible use strong action verbs. Humans do things, interesting humans do interesting things, and people generally read what they find interesting.

I practice this a lot, and here's how:

I’m going to set my watch timer for five minutes (it would usually be twenty or thirty, depending on my mood) and write what I can in that time, focusing on images and action verbs. I have no plan to start with except some cues. The cues could be anything. I have a Krakauer book on my desk with cloud-covered mountains on the cover, and a coffee-table fashion book nearby that was left open to an image of a runway figure in a red cloak, so I’ll use these: cloudy mountain, red cloak. If you want to play along, pick yours, the first thing you see.

Okay, be back in five…

Here’s what I hacked out, with just a minimum of punctuation added and a few misspellings corrected:

She climbed up out of the lower clouds and crested the high ridge and glimpsed his red cloak through the mist and smiled. His head was bent in prayer and she was certain he did not see her as she broke into a run. Her heart pounded in her breast and her feet seemed to float across the damp and slippery stone and when she came to the narrow gulf between them, she leapt across it and raised her arms mid-flight and landed with her weight behind the edge of her axe on his exposed neck. The king did not move from where he knelt, but his head hit the slope and rolled away, bouncing like a loosed stone before plunging over the edge and into the gray abyss. Breathless and wild-eyed, she cast down the axe and took up the king’s sword from where it lay and raised it high into the mists and opened her mouth to scream in triumph, but the scream never came. A flash of lightning appeared at the sword’s tip and welded her ringed fingers to its hilt and boiled her blood as it traveled through her on its path to the earth, setting fire to her shoes and blowing off the soles of her feet.

Far down in the village stables, the old man’s eye caught the flash and he looked up from the horse he was shoeing. He had a foreboding feeling, though the mountains were too curtained in cloud, and too distant even if they hadn’t been, for him to see that the retreating streak of lightning that had tethered itself briefly to his fate, now released and drawn back to the heavens, left behind the charred and smoking body of his only daughter at the knees of her murdered lover and his king. This he could not see and could not yet know, though he would. But the following peal of thunder somehow conveyed, at least to the farrier’s soul, that he was now childless and that the hooves of the royal horse he labored over answered no longer to any living man and that the stables themselves and all around belonged now to the war soon descending upon a headless realm. Deep down he knew, but even knowing, he looked away from the mountain and returned as he always had and always would to what he knew beyond all knowing, his work.

Is this great writing? No. It reads a little frantic and maybe even too macabre, especially for a Wednesday morning. But it’s a useful exercise, and there’s a lot happening. I have no idea who these people are or why they’re doing what they’re doing or even from what dark corner of my mind they sprang. I’ll probably never know. But the act of writing against a ticking clock with a focus on strong verbs called them forth from nothing and set them in motion. And once someone does something interesting, we usually want to know why. So now the writer has writing to do.

Sometimes these exercises and others like it lead to characters appealing enough to pursue and flesh out, leading in turn to a book, or if not, at least to a few weeks spent exploring them on the page. And even if it all goes nowhere, it’s never wasted. It’s writing. Writing itself can be a verb. The writing that results is just the evidence of the work, and in a way was born of the earlier reading and listening and living. It’s the fruit of something sowed in another season and then forgotten, a thing begotten that cannot be engineered or even explained. At least not by me.

And that’s my two cents, and today it’s free. You can get a lot more for two bucks.

Ryan.

###

P.S., I sent this piece off to my wife just now, which I rarely do, fearing I might have run long or come across uncharacteristically direct, and hoping to get her thoughts before publishing. She replied almost instantly with “TL;DR,” which is her shorthand for “too long; didn’t read.” And this is just one of the many reasons I love her.

An audio recording of this essay can be found here:

Captions, how do I hate thee? (Plural of thee is … I dunno.). Captions for anything audible ruin the experience. No level of greatness in the visual product can overcome their taint.

Your admirer,

Caption Obvious

Enjoyable and informative. Seems being a writer involves more than writing and less than performing, yet equal commitment.